Immediately after the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority filed an historic lawsuit against over 100 oil and gas companies, Governor Bobby Jindal “demanded” the authority drop the suit. Curiously, though, neither he nor any member of his administration have ever criticized the actual merits of the litigation; instead, Jindal and company seem to be infuriated with the idea that lawyers may make money off of this. “This is nothing but a windfall for a handful of trial lawyers,” Jindal said. “It boils down to trial lawyers who see dollar signs in their future and who are taking advantage of people who want to restore Louisiana’s coast. These trial lawyers are taking this action at the expense of our coast and thousands of hardworking Louisianians who help fuel America by working in the energy industry.”

Governor Jindal, in doing the bidding of the oil and gas industry, failed to mention that the only way these “trial lawyers” could make a significant amount of money from this litigation is if they win. And if they win, Louisiana stands to gain billions that would be used for coastal restoration. If they lose the case, they make nothing. And if, for some political reason, the lawyers, whose contract was unanimously approved by the authority, are forced to abandon the lawsuit, they can only be compensated for the work they’ve already done. It’s a standard contingency fee agreement. Governor Jindal’s contemptuous comments about “trial lawyers” not only reflect a cynical politicization of the most critical issue in Louisiana, they also promote an insidious and ignorant disdain for the rule of law, the legal profession, and the judicial process.

So, it is supremely ironic that less than 24 hours after Jindal issued his scathing attack on lawyers, the Associated Press reported that, in 2012, the Jindal administration had steered over $1.1 million in no-bid state legal contracts to Jimmy Faircloth, Governor Jindal’s former executive counsel. Suffice it to say, Mr. Faircloth, who donated $25,000 to Governor Jindal’s campaigns, made significantly less than $1.1 million a year when he served as Jindal’s chief lawyer. Mr. Faircloth resigned from the Jindal administration in order to run an unsuccessful campaign for the Louisiana State Supreme Court, and shortly after his defeat, he was fined by the Louisiana State Ethics Board for violating ethics rules. Quoting from The Times-Picayune:

Faircloth returned to private practice with his new law firm, and within three months of the election loss, in January 2010, he was hired to represent the Louisiana Tax Commission, led by Jindal appointees. He canceled the legal services contract a few months later, after questions were raised about whether he had waited enough time under the law to do the work.

The governor’s executive counsel is among those public employees prohibited from entering into state contracts for a year after leaving the job under Louisiana’s ethics laws. At the time, Faircloth said he didn’t believe the tax commission contract was prohibited, but he was later fined $1,000 by the Board of Ethics for violating the law. The fine was suspended as long as Faircloth remained in compliance with ethics laws.

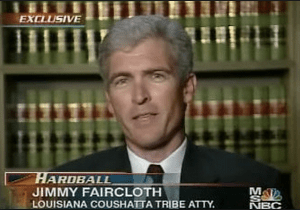

Indeed, Faircloth’s professional ethics had come into question years before, when it was revealed by The Times-Picayune that leaders of the Coushatta tribe accused him of pressuring them to invest millions into an Israeli technology company that employed his brother. Quoting:

Before becoming executive counsel this year to Gov. Bobby Jindal, Alexandria lawyer Jimmy Faircloth was a key figure in a high-risk business venture that is sparking new controversy in a Louisiana Indian tribe still shaken after becoming the victim of a national scandal.

From 2005 to 2007, Faircloth advised the Coushatta Indians to invest $30 million in a formerly bankrupt Israeli technology firm called MainNet, which so far has shown no financial return for the tribe and is dependent on monthly installments of Coushatta cash. The company also hired Faircloth’s brother, on the attorney’s suggestion, after the tribe began investing.

In the most recent Associated Press article about Mr. Faircloth, both Faircloth himself and members of the Jindal administration reference his considerable legal acumen as justification for awarding him no-bid contracts. And while Mr. Faircloth may, in fact, be a skilled lawyer, the truth is that he has been on the losing end of practically every single high-profile case he’s litigated on behalf of the Jindal administration.

But, in fairness, that’s not the real issue. Within the span of only three years, Jimmy Faircloth went from making less than $200,000 a year as Governor Jindal’s executive counsel to making more than $1.1 million a year representing Governor Jindal and his administration as a private attorney. It’s staggering.

Make no mistake: I’m not suggesting or implying that Mr. Faircloth has ever engaged in anything illegal. I don’t fault him for being savvy or financially successful. I do, however, think that his no-bid legal contracts deserve scrutiny, and at the very least, they represent the Jindal administration’s fundamental hypocrisy on the issue of “trial lawyers” who make “windfall” profits on the public dole.

Consider this: When Bobby Jindal “demanded” that the levee protection authority drop its lawsuit, he improperly claimed they had acted outside of their scope by hiring attorneys without his permission. Quoting (bold mine):

“By filing this suit against nearly 100 companies, the SLFPAE has effectively taken on the role of the governor, the attorney general, the Department of Natural Resources and the CPRA in determining the state’s policy on coastal issues,” the release said.

The release also said state law requires any special attorney or counsel representing a state board or commission to be paid “solely on written approval of the governor and the Attorney General and pay only such compensation as the governor and the Attorney General may designate in the written approval.”

“The governor did not approve this contract — nor would he have approved this contract,” the release said.

In a statement responding to Jindal, Barry defended the authority’s action in filing the lawsuit and challenged the governor’s allegation that it had been improperly influenced by trial lawyers.

But in response to the inquiries about Faircloth’s no-bid contracts, the Jindal administration took a completely different approach (bold mine):

When asked if the governor’s office advised agencies to contract with Faircloth for legal work or sought to steer work in his direction, Jindal spokesman Sean Lansing initially said no. He said the governor’s office doesn’t direct agencies to hire specific attorneys.

Told that others spoke of Jindal’s office suggesting Faircloth’s firm for the education cases, Lansing later revised his response.

“We have recommended Jimmy in certain circumstances because he is a great lawyer, but at the end of the day, it is up to agency heads to decide on the lawyer who represents them,” he said.

Yeah, sure it is.

Here’s how I put it to Kyle Plotkin, Governor Jindal’s communications director:

Reblogged this on The Daily Kingfish and commented:

“Money for nothing,” checks for free. @BobbyJindal’s fav attorney gets showered in taxpayer dollars. #makingitrain

Don’t know if it is legal, but it sure does smell quite a bit.

I see that as of this date, the SELAFPA has not yielded to lil Bobby’s demands. 🙄

The success of red sole shoes became more profound in 1980, when the company already occupied all four floors of the Manhattan building where it was located.